Английский язык. English in dentistry : учебник для студентов стоматологических факультетов медицинских вузов / Под ред. Л.Ю. Берзеговой. - 2009. - 272 с.

|

|

|

|

LESSON 8. AT THE DENTIST'S. DENTAL HISTORY. GRAMMAR: THE USE OF PRESENT SIMPLE IN IF- AND WHEN- CLAUSES TO DENOTE A FUTURE ACTION

Exercise 1. Read and translate into Russian the following words and word combinations of Latin and Greek origin:

dental inspection, orthodontics, to consult an orthodontist, to drill, cavity, abscess, to diagnose, crowns, prosthetics department, dental mechanic, malocclusion, hygiene, to protect.

Exercise 2. Practice the pronunciation of the following words: toothache, trouble, aching, decayed, gone, neglected, put, pull, artificial, dentures, false, mechanic, overcrowded, malocclusion, deaden, pain, hygiene.

Exercise 3. Learn the active vocabulary to the text:

dentist стоматолог

dental therapist стоматолог-терапевт

oral surgeon хирург - стоматолог

to have some trouble with a tooth что-то беспокоит (о зубах)

to become loose расшатываться

to undergo a dental inspection пройти осмотр стоматолога

a tooth is neglected (far gone) зуб запущен

to cleanse a tooth почистить зуб

to drill a tooth сверлить зуб

to put in a filling поставить пломбу

(to stop a tooth, to fill a tooth)

to pull out (extract) a tooth удалить зуб

to deaden pain обезболить

dentures / false teeth искусственные зубы

crown коронка

bridge мост

outstanding / instanding teeth прогнатия, прогения

overcrowded teeth скученные зубы

malocclusion неправильный прикус

to correct malocclusion исправить неправильный прикус

prosthodontist протезист

orthodontist ортодонт

dental mechanic/prosthetist зубной техник, протезист

Exercise 4. Read and translate the text into Russian.

AT THE DENTIST'S

Every citizen of Russia undergoes regularly dental inspection and treatment in district stomatological polyclinics. There are three main departments in such polyclinics: a department of therapy, oral surgery and orthodontics and prosthetic dentistry department. Some laboratories and X - ray rooms are also attached to every dental polyclinic.

If you have some trouble with your tooth or a bad toothache you should consult a dentist. He will examine your teeth and if the aching tooth is not far gone he will stop it. He'll clean and drill your tooth and then put in a filling. If your cavity is neglected (far gone) and it hurts you the dentist will treat your tooth. In case the tooth is too bad to be stopped or treated, the dentist

will pull it out (extract a tooth). Before extracting a tooth he will apply some anaesthetic or give an injection to deaden the pain.

If you have some inflammation or an abscess in your mouth, if the teeth become loose and gums bleed, you should consult an experienced specialist. He will diagnose your case and prescribe a proper treatment. If an operation must be performed in the mouth cavity, a qualified oral surgeon will operate on you. If you need dentures, bridges, some false teeth or crowns you must consult a dental mechanic and he will do everything you need. If you have instanding or outstanding teeth, overcrowded teeth or malocclusion, you must consult an orthodontist and get it corrected.

Regular visits to a dentist, once or twice a year, proper oral care and good eating habits (a limited consumption of sweets in the first place) will protect you from many dental diseases.

VOCABULARY EXERCISES

Exercise 1. Give the English equivalents to the following words and word combinations:

пройти осмотр стоматолога, терапевт-стоматолог, хирург-сто- матолог, зуб запущен, почистить (посверлить) зуб, запломбировать зуб, удалить зуб, искусственные зубы, коронки, мосты, прогнатия / прогения, неправильный прикус, ортодонт, протезист.

Exercise 2. Give the synonyms for:

to stop a tooth, to extract a tooth, a tooth is far gone, if, a dental examination, an aching tooth, to prescribe a treatment.

Exercise 3. Rephrase the parts in bold type in the following sentences:

1. One must undergo dental inspection once or twice a year.

2. If a tooth is not far gone the doctor will treat it.

3. Тhе dentist will not put in a filling today, he will do it in two days.

4. This tooth can't be stopped, it must be pulled out.

GRAMMAR EXERCISES

Exercise I. Translate the following sentences paying attention to the use of tenses in IFand WHENclauses:

1. If the weather is good on Sunday, we shall go to the country.

2. When we get back home, it'll be dark already.

3. The doctor will make his diagnosis when he has all the laboratory findings.

4. If you consult your dentist regularly you will have no dental diseases.

5. If you can't come tomorrow, you will have to come next week.

6. You needn't worry. If the tooth can be treated nobody will extract it.

7. I don't know when he will come.

8. I wonder when he will come.

9. Nobody can say if the train will arrive at 10 or 11 a.m.

Exercise 2. Open the brackets using correct forms of the verbs:

1. Surgeons (extract) teeth that cannot be (treat).

2. The examination of the oral cavity (perform) by the prosthodontist when people want denturues.

3. Bridges, crowns, dentures and artificial teeth (make) of different materials now.

4. Oral therapy (include) such procedures as cleansing and drilling a tooth before filling it in.

5. To have healthy teeth people must (undergo) dental examination once or twice a year.

Exercise 3. Translate the following sentences into English:

1. В стоматологических поликлиниках работают разные специалисты: терапевты, хирурги, ортодонты и протезисты.

2. Если у Вас болит зуб, Вам следует обратиться к терапевту-стоматологу.

3. Если зуб не запущен, его можно вылечить, т.е. почистить, посверлить и поставить пломбу. Запущенный зуб обычно удаляют.

4. При удалении зубов применяется анестезия. Хирург делает обезболивающий укол.

5. Чтобы не было проблем с зубами, посещайте стоматолога один или два раза в год для профилактического осмотра.

SPEECH EXERCISES

Exercise 1. Answer the questions to the text «At the dentist's»:

1. What departments are there in a stomatological polyclinic?

2. What must a person do if he has a bad toothache?

3. What does a dentist begin his examination with?

4. What does he do if a tooth can be treated?

5. And what about the cases when a tooth is far gone?

6. What conditions need surgical treatment?

7. In what cases do people have to consult an orthodontist?

8. What is the primary cause of many dental diseases?

9. What kind of orthodontic and prosthetic services are available at our dental polyclinics?

Exercise 2. Agree or disagree with the following statements using the phrases: Model: Yes, that's right (true). No. I don't think so.

1. There are no stomatological clinics in Russia, are there?

2. Before extracting a tooth a surgeon gives a patient some anaesthetic, doesn't he?

3. If a tooth is not too bad it must be pulled out, mustn't it?

4. If you need artificial dentures or crowns you must consult a dental surgeon. Isn't that so?

5. Too much sweets will do your teeth no harm, will they?

6. Рrореr oral hygiene and good eating habits are not important for the development of dental diseases, are they?

Exercise 3. Ask your dentist about: WHY your tooth hurts you so much

WHETHER (IF) your tooth can be treated or not

it can be filled or not

it must be extracted WHERE you can find the laboratory

HOW LONG it will take you to have your teeth treated WHEN you must come next time

WHAT you must do to protect yourself from tooth decay

Exercise 4. Read the dialogue and be ready:

1) to speak on behalf of a) a doctor, b) a patient

2) to act out the situation, retell it in indirect speech

A DIALOGUE

Doctor (D): How do you do, Mr. N.? What can I do for you? Patient (P): I've got a bad tooth that aches all day and night. D: Let me have a look at it. Well, I'm afraid it's too late to have it filled, the

only thing I can do now is to extract it. P: (pretending to be calm): All right, Doctor, but not without an injection. D: (filling a syringe and getting his instruments ready): Certainly, Mr. N., it

won't hurt at all, just keep your mouth wide open.

D: (gives Mr. N. an injection in the gum, waits a couple of minutes, gets hold

of the tooth and extracts it): It's all over. Was it so bad? P: (with a sigh of relief): Not at all, thank you very much.

Exercise 5. Try to complete the dialogue below using the Active Vocabulary. Patient: ...

Doctor: How do you do. What's the trouble? Patient: .

Doctor: Well...Take this chair...Open your mouth, please. Here is a cavity

that needs filling. Patient: .

(The doctor is treating a cavity.)

Doctor: Now it won't give you any more trouble.

Patient: .

Doctor: Good-bye.

Exercise 6. Read and translate the article from the newspaper into Russian. Answer the questions after the article.

HOW HALF OF DENTISTS TURN THEIR BACKS ON NHS PATIENTS

More than half of English dentists have closed their doors to NHS patients, a survey reveals.

The research found 51 per cent of dentists were only taking on patients if they agreed to go private.

In some areas, the situation is so bad that only 15 per cent of dentists are taking on NHS patients, the study by consumer magazine «Which?» showed.

The research comes a week after Tony Blair admitted for the first time that Labour had broken its pledge to ensure everyone had access to an NHS dentist.

Liberal Democrat health spokesman Norman Lamb said the figures showed NHS dentistry is 'becoming a thing of the past'.

'What is most worrying is that many people on low incomes are effectively excluded from dental care' he added.

'One 80-year-old woman who came to me needed teeth taking out and new false teeth putting in.'

'She was told that would cost between 500 and 800 to have done privately - because she can't get an NHS dentist.'

Researchers from «Which?» posing as potential patients contacted 466 dentists.

The survey showed the worst area for access was the North West, where only 13 per cent of dentists are taking on NHS patients.

Following closely behind were Yorkshire and the Humber on 15 per cent, and 16 per cent in the South Central region. The best areas for NHS dentists were the West Midlands, on 63 per cent, and London on 59 per cent.

Those living in rural areas suffer the most - just 16 per cent of dentists in the countryside provide NHS treatment, compared with 39 per cent in towns and cities.

The situation was even worse for NHS emergency appointments, which were offered by only 5 per cent of dentists in the North West and South West.

Last month a survey by Citizens Advice found around two million people in England who would like access to NHS dentistry are unable to do so. Two thirds of them simply go without treatment rather than going private.

Recent surveys by «Which?» have also highlighted patients' dissatisfaction at the state of the rest of the health service.

Only 18 per cent were happy with the quality of hospital food, with 29 per cent of patients - and 57 per cent of new mothers - feeling hungry after meals. Another surveyof2000 patients found many did not know where to turn for out-of-hours care, with only two in five calling the NHS Direct helpline.

Frances Blunden of «Which?» said: The Government has allocated enormous amounts of money into the NHS but on the ground the public are seeing cuts in services and considerable difficulties getting treatment.

'In dentistry we have found that where needs are not currently being met, people are either putting off having treatment or are being forced to go private.' Tory health spokesman Andrew Lansley said: 'After ten years of Labour's financial mismanagement patients are being told they can't have operations, nurses are on the brink of strike action, maternity units and accident and emergency are being treatened with closure, and 10 000 talented junior doctors are left without jobs'.

Tony Blair and health secretary Patricia Hewitt are due to defend their record in front of the King's Fund think tank today.

Notes:

go private зд. получать лечение платно, частным образом

the NHS the National Health Service

health spokesman представитель (партии) по вопросам здраво-

охранения

think tank зд. группа разработчиков

1. Is it easy for patients to receive NHS dental treatment?

2. Do dentists eagerly take NHS patients?

3. Is the situation the same in all areas of England?

4. What is the situation with people on low incomes?

5. Can people get emergency NHS dental treatment?

6. Are there many people in England who would like to have access to

NHS dentistry?

7. What do people think about having to go private?

8. Are people satisfied with the quality of in-patient hospital treatment?

9. Does the Government do much to improve the situation?

Exercise 7. Translate Part 1 of the text «Making Clinical Decisions» using a dictionary if necessary.

a/ Before you start try to give good Russian equivalents for the word combinations given below paying special attention to words in italics.

b/ Answer the questions that follow the text

1 to attend a dentist, 2 to attend for treatment, 3 to seek/accept one's advice, 4 to feel detached from (the process), 5 to manage one's health, 6 without this involvement by the patient, 7 to encourage the involvement of patients, 8 the shared involvement, 9 along with this comes the responsibility, 10 in the final analysis, 11 to make sacrifices of (time, effort, finance), 12 shortly, 13 this engenders trust in patients, 14 once the professional-client relationship breaks down, 15 the management of a condition, 16 a large part of the chapter is taken up with..., 17 to enable a dentist (to give advice), 18 to take a much more substantial decision, 19 in many cases, judgment is needed to be applied, 20 if a diagnosis is straightforward, 21 the process could be undertaken by computers, 22 clinicians seek second or even third opinions, 23 to adopt some middle course, 24 to reach a final decision as to the best advice to offer the patient

MAKING CLINICAL DECISIONS

Part One

WHO MAKES THE DECISION?

Gone are the days when most patients attended their dentist or other professional adviser, sought and accepted his or her advice without question, and felt almost detached from the process. Although patients used to do things «under doctor's orders», many now take a much more lively interest in the management of their own health. Along with this involvement, which many patients seek and which should be encouraged in those who do not, comes a responsibility for participating in decisions about their own welfare. In the final analysis, it is patients who will decide whether they will attend

for treatment, whether they will clean their teeth effectively, and what sacrifices of time, effort, and finance they are prepared to make.

A dentist's role is to offer advice and, if the advice is accepted, provide treatment. This advice can usually be classified as follows:

• Diagnosis

• Prognosis

• Treatment options

• Prevention of further disease.

These matters will be dealt with in more detail shortly, but first it is necessary to understand the nature and status of this professional advice.

The professional-client relationship is special in that professional people take upon themselves the duty of setting their client's interests above their own. It is this aspect of professionalism which engenders trust in patients and explains why they so often accept the advice of the dentist. Once this professional relationship begins to break down, as it does if the dentist puts his/her own interests before that of the patient then the patient's confidence is lost and he/she begins to mistrust the dentist's advice.

In order to give advice the dentist will need information, and a large part of the chapter is taken up with describing what this information might be, and how it should be collected and collated. In some cases this information alone will be enough to enable the dentist to give advice and take a decision. However, in many cases another element, judgment, will need to be applied. If all diagnosis and treatment planning were straightforward, so that a given set of facts always resulted in the same treatment plan, the process could, and by now probably would, be undertaken by computers. Judgment based on the clinician's own experience and that of others is a second element in the essential nature of a professional person. Using the terminology of British law, some of these judgments can be made «beyond reasonable doubt» but others have to be made «on the balance of probability». It is the skill and care with which these judgments are made that distinguishes the really good dentist from the merely good dentist. In difficult cases many experienced clinicians seek second or even third opinions, discussing the case with colleagues before reaching a final decision as to the best advice to offer the patient.

Many decisions are rather routine in their nature and become automatic with practice, rather like the subconscious decision to press the accelerator to drive the car faster. While learning to drive, this decision, like many similar decisions in dentistry, has to be considered consciously. Other decisions may be slightly more difficult, such as whether all the dentine caries in a

tooth must be removed and whether fissure caries has extended to the point where it should be restored or not, these decisions are always made at the conscious level. Then there are the much more substantial decisions which sometimes have to be made - for example, whether to advise a patient to have all his or her teeth extracted, or to have them all crowned or extensively restored, or to adopt some middle course of a few extractions with a simpler level of restorations and perhaps a partial denture.

THE FOUR MAIN DECISIONS

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is the recognition of a disease. Sometimes a bald statement of the diagnosis is sufficient, or example, amelogenesis imperfecta. In most cases, however, the diagnosis should include the extent, location, and other characteristics of the disease. For example, a diagnosis of caries or periodontal disease is not enough without describing where it occurs and how extensive it is.

Prognosis

The prognosis of a condition is the estimate of what will happen if it is not treated and what the consequences of treatment will be. Therefore the prognosis for an early enamel carious lesion is good if appropriate preventive measures are taken, whereas the prognosis for maintaining the vitality of the pulp if caries is so extensive that symptoms of pulpitis arise is poor. However, in the latter case, if other conditions are favorable, the prognosis for keeping the tooth if root canal treatment is carried out is good.

Treatment options

This often seems to be the most important decision, particularly for the patient, in that it affects what will be done. However, it is based so fundamentally on the first two decisions, diagnosis and prognosis, that it is, in reality, no more important, and often less so, then they are.

Further preventive measures

The long-term success of treatment is dependent in many cases on the patient's willingness and ability to co-operate in preventing further disease. A decision about the likelihood of this being effective should be attempted before the definitive treatment plan is decided, in particular if extensive treatment is contemplated. Thus the aim of an initial treatment plan may be to stabilize active disease, assess its cause, and start preventive measures. The patient's response to this initial treatment will be an important factor when planning subsequent care.

Questions:

1. What must a diagnosis be based on?

1. In what cases is prognosis good and when can it be poor?

2. How important is treatment compared to diagnosis and prognosis?

3. What does the success of a treatment depend on?

4. When should a definitive treatment plan be decided?

5. What may the aim of an initial treatment plan be?

Exercise 8. Read and translate Part 2 of the above-mentioned text so as to be able to sum up the aide-memoire for the history and examination of a new patient.

Part Two

THE INFORMATION NEEDED TO MAKE DECISIONS AND HOW IT IS COLLECTED AND RECORDED

Part of the skill of an experienced clinician is to decide what information is needed, and to acquire it accurately and rapidly so that he or she is in the best position to give good advice without undue delay. Some clinicians adopt a «data gathering» approach in which, using check-lists, they try to accumulate all the information which would conceivably be of some relevance about a patient.

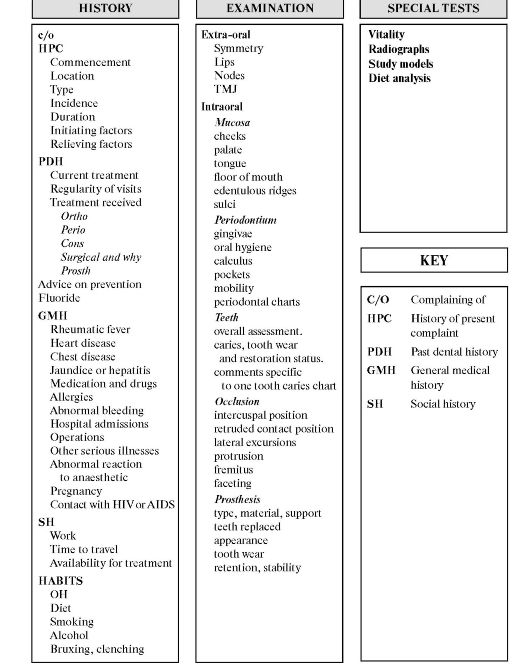

Some information is essential for all patients, some is useful for most, and in others a very detailed investigation of a narrow field of interest is necessary in order to reach a diagnosis or make one of the other decisions outlined above. Figure 1 shows a list of information which may be helpful to a student when first meeting patients. It is not meant to be followed slavishly but it is a useful aide-memoire for the inexperienced.

However, it is dangerous to begin the examination of a patient without first ensuring that it will pose no risk to either the patient or the dentist. For this reason a full medical history should be taken before the examination, irrespective of any other history.

Lists such as the one in Fig. 1 are oversimplification and suggest that the entire history should be taken first, followed by the examination of the patient. Some dentists even do this in two separate areas of the surgery, attempting to separate the conversational and clinical aspects of the process. This is often not practical and indeed may be undesirable. It is much better to mix the two processes together and maintain a steady conversation with the patient before, during, and after the examination, pausing to take notes or, better still, dictating them to the dental nurse or onto a tape as the process continues.

The reason for this is that until the dentist has made an initial examination of the mouth it is often not possible to tell what detailed line of questioning to pursue. For example, if the patient complains of discolored teeth, a quick examination will show whether this is surface or intrinsic stain. If it is surface stain there is no need for questioning on the administration of tetracycline in childhood or the ingestion of excessive fluoride. Another common example is the patient who complains about his teeth «crumbling away». This may be the result of caries and failing restorations, tooth wear, or a developmental defect. Again, a quick examination will show which approach to the dietary history is likely to be most helpful - to pursue a detailed history relating to sugar or a detailed history relating to erosive materials - or whether, if it is a developmental disturbance, diet has no bearing on the matter at all. It is necessary here to describe the history and examination process in some sort of order, even if this order will seldom be followed comprehensively in practice.

Exercise 9. Read and translate Part 3 of the text. Before you do, translate the sentences that follow, paying special attention to words in italics.

1. This information is essential and it should always be checked for accuracy.

2. The patient's occupation may have a bearing on the condition itself (for example, industrial erosion) and may affect availability for treatment.

3. Direct questioning is usually unhelpful while attitudes may become apparent during conversation, particularly when past dental treatment and experience are discussed.

4. A question such as 'Do you think you have a sweet or a sour tooth?' can often elicit valuable information about attitudes as well as facts.

5. This is an example of how history and clinical examination go together to produce information relevant to the particular patient.

6. Any apparent discrepancy between what patients say that they do when they clean their teeth and the clinical condition may be cleared up by asking them to bring brush and paste to the surgery.

7. Previous treatment indicates susceptibility to disease as well as attitudes towards dental care.

8. It is thus possible to build up a picture of past dental history which may include caries experience, restorative treatment received, susceptibility to periodontal disease, etc.

9. Attitudes to dental health, either positive or negative engendered within the family may have an important bearing on the condition with which the patient presents. The same is true of the patient's social background.

Fig 1. Aide-memoire for the history and examination of

Fig 1. Aide-memoire for the history and examination of

the new patient.

Part Three

CASE HISTORY

About the patient

Name, address, telephone and Fax numbers

This information is essential and it should always be checked for accuracy. It is quite possible to have two people with the same name in the waiting room or the practice, and only careful and routine checking will prevent serious mistakes being made.

Age, sex, occupation

Age will have considerable bearing on the state of dental development in younger patients and is important for a variety of reasons at other ages. The patient's sex usually has no bearing on the treatment advised, although it is usually recorded to avoid confusion. It should not be assumed that female patients are more concerned with their appearance than male patients. The patient's occupation may affect availability for treatment.

Attitude and motivation to dental health and treatment

Whereas information about age and occupation are easily obtained by direct questioning, assessment of attitude to dental health and motivation is more difficult. Direct questioning is usually unhelpful because the patient will tend to answer the questions in a way which will «please» the dentist. However, attitudes may become apparent during conversation, particularly when past dental treatment and experience are discussed.

Diet

Since diet plays a major role in dental caries and can be of importance in tooth wear, a discussion about diet is often useful. A question such as «Do you think you have a sweet or a sour tooth?» can often elicit valuable information about attitudes as well as facts. For instance, the way that the patient answers such questions may reveal whether he or she appreciates the relevance of diet to dental disease and whether modification of diet has been tried in the past. However, a detailed examination of diet is reserved for those with specific caries or tooth wear problems which will only become obvious after clinical examination go together to produce information relevant to the particular patient.

Habits

It is useful to enquire about tooth cleaning habits and the toothpaste used, but other habits may also be relevant; for example, smoking will increase the likelihood of surface stain on teeth. Following clinical examination further questions may be needed; for example, a particular pattern of

tooth wear may suggest questions about grinding habits, an erosive diet, or alcohol consumption.

Any apparent discrepancy between what patients say that they do when they clean their teeth and the clinical condition may be cleared up asking them to bring brush and paste to the surgery.

Willingess to meet fees and other expenses

Most dental treatment involves the patient in some expense. Usually it is not possible to estimate the fee or the amount of time involved until an outline treatment plan is established. Sometimes this «ideal» outline plan will be too costly for the patient and an alternative might have to be sought. It is important to establish this at an early stage before too much time is spent in detailed planning.

About the patient's general condition and health

Here a check-list is useful and questions are usually asked, and followed up when necessary, about the following:

• history of heart or chest disease

• current (or recent) medication

• allergies

• any difficulty in the arrest of hemorrhage after extraction or injury

• previous hospital admissions

• other diseases

• pregnancy

• contact with HIV or AIDS

When these questions are answered positively it may be necessary to refer to the patient's general medical practitioner or to arrange further investigations (for example, blood tests) before proceeding with treatment.

The patient's reason for attendance

Some patients have an urgent problem such as pain or trauma, while other attend for a routine examination without particular symptoms. When symptoms are present the patient should be encouraged (without the use of leading questions) to describe these as clearly and in as much detail as possible.

Past dental history

A patient's past dental history can be of considerable assistance. Previous treatment indicates susceptibility to disease as well as attitudes towards dental care. For instance, the question «Have you had many fillings done?» may lead the patient to explain that most teeth have been restored. It this question is then followed up by asking whether most of the

fillings are old or whether they have to be replaced regularly, the information obtained may indicate whether the patient is currently a high caries risk. It is thus possible to build up a picture of past dental history which may include caries experience, restorative treatment received, susceptibility to periodontal disease, periodontal treatment received, extractions and the reason for the loss of the teeth, and information about prosthetic replacements.

Family and social background

Where an inherited condition is suspected, clearly the distribution within the family is important. In other cases attitudes to dental health, either positive or negative, engendered within the family may have an important bearing on the condition with which the patient presents or upon acceptance of treatment. The same is true of the patient's social background. Other aspects of the social history - for example availability for long appointments - will also determine the type of treatment.

Exercise 10. Translate Part 4 of the text into Russian. Complete sentences that follow it with words and expressions from the text that are given in brackets.

Part Four

EXAMINATION

General appearance

The patient may appear nervous or relaxed, fit and well or elderly or ill, clean and tidy or dirty and disheveled. These or similar observations will guide but should not dictate treatment. It takes time to get to know people and instant judgments are unwise. For instance, a neglected general appearance does not necessarily mean that the person does not care about his dental health.

Factors which predispose to cross-infection

Some people - for example, drug addicts, homosexuals, or heavily tattooed patients - are more likely to be carriers of the hepatitis B virus and HIV (human immunodeficiency virus).

The extra-oral facial appearance

The temporomandibular joint and lymph nodes should be palpated. Any obvious asymmetry is noted and the lips are examined. Such things as injuries or scars on the lips may be accompanied by dental injuries. Where the patient's problem involves appearance, the dentist will make his or her own assessment of this while listening to the patient.

The mouth in general

Oral hygiene is relevant in both periodontal disease and caries. A general impression of whether the mouth is well cared for by both the patient and previous dentists is useful, but patients do sometimes increase their dental awareness considerably and previous neglect need not imply future neglect.

Specific areas of the mouth

The soft tissues

A routine examination of the inner aspects of the lip, the tongue, and the buccal and lingual sulci should be made at all examinations since, amongst other things, early neoplastic change can be detected and early treatment can be life-saving.

The periodontal tissues

A general assessment of the state of periodontal health is always necessary. This will include oral hygiene; the presence of both supraand subgingival calculus, the health and position of the gingival tissues, the presence of pockets, and whether there is bleeding on probing and mobility of teeth. In many cases a more detailed periodontal examinations needs to be undertaken.

Caries experience: past and present

Again, a general impression can be gained of the extent of carious lesions and previous restorations. It is reasonable to assume that restorations are most commonly the result of caries but, of course, other conditions may also have been responsible.

Other conditions affecting the teeth

These include trauma, tooth wear, dental defects, missing teeth, and malpositioned teeth.

The occlusion

First, the static relationship of the teeth in intercuspal position (ICP) should be examined to determine the horizontal and vertical overlap of the anterior teeth (overjet and overbite), together with the relationship of the posterior teeth. Next, and perhaps more importantly, the way in which the teeth function against each other in forwards, backwards, and lateral movements of the mandible should be examined. This is often relevant to the decision as to how to restore a tooth. If a cusp functions vigorously against an opposing tooth when the jaw moves, then it may need protecting in some way by the restoration, but if it immediately discludes in all movements of the mandible, it may not.

Dentures

The presence and nature of dentures should be noted. It is important to decide whether dentures are satisfactory or in need of replacement.

Diet analysis

The past and present diet can be investigated by questioning and by completing a diet sheet.

Salivary analysis

In patients with a high caries incidence, the salivary buffering capacity may be tested. Also, counts of Streptococcus mutans and lactobacillus in the saliva may be used to monitor the caries risk and the success of a caries prevention program.

Sentences to be completed:

1. It.........time to get to know people and instant judgments are.........

2. Oral hygiene is..........in both periodontal disease and caries.

3. A general impression is useful, but patients do sometimes increase

their ............ considerably and previous neglect need not imply future

neglect.

4. A....... examination of the mouth cavity should be made at all dental

examinations since early treatment of some disease can be life-saving.

5. It is important to decide whether dentures are satisfactory or in need of............

6. In patients with a high caries........., the salivary pH may be tested. (routine, incidence, unwise, dental awareness, relevant, takes, replacement)

Exercise 11. Home Reading Material. Translate Part 5 of the text MAKING CLINICAL DECISIONS into Russian. Answer the questions that follow.

Part Five

THE HISTORY AND EXAMINATION PROCESS Examination Process

As stressed earlier, the full history is not usually completed before the examination starts. Although there are many variations, a common pattern of history and examination would proceed as follows:

• reason for attendance

• medical history

• initial preliminary examination

• initial assessment of the patient's general oral and dental condition and the specific problem, if there is one

• further conversation to effect more details of the symptoms (if there are any), and the background to the problem which is likely to be relevant - for example diet, social history, etc.

• further detailed examination

• general assessment of the patient's dental awareness and expectations

• special tests

• start the treatment planning process

Whatever sequence is used for a particular patient, it is helpful if the findings are recorded in a systematic way. The record must always be made while the patient is present, and the need for a contemporaneous record cannot be overstressed both in the interests of accuracy and also for medico-legal reasons.

Planning the treatment

Treatment should follow a planned course in all cases. This is not to say that the plan is unalterable, and the temptation to write down a treatment plan as a prescription and then follow it without further thought or revision should be avoided. It is necessary to maintain constant vigilance for changes in the clinical circumstances, the patient's response to treatment, and the success of earlier stages in the treatment.

The general approach to treatment planning should be one of problem solving. This seems obvious, but is not always as simple as it sounds. One set of circumstances - for example, a mild disturbance in the appearance of a tooth - might be a real problem to one patient, causing great distress, and yet go unnoticed by another.

Cosmetic problems like this can be regarded as the patient's problem and he or she will ultimately decide whether they want treatment or not. Other problems are more the dentist's. To continue with the same example, the dentist must decide between recommending a composite restoration, a facing of composite or porcelain, or a crown. The final decision is taken jointly between patient and dentist and illustrates another important principle of treatment planning. The patient must be properly informed about treatment alternatives and must give informed consent to the treatment.

Treatment plans can conveniently be divided into «simple» and «complex». A simple treatment plan is by far the most common and is all that is usually required for patient and recall visits, sometimes over many years of maintenance of a good standard of dental health. In such cases the dentist is monitoring health. However, there is a danger of both dentist and patient being lulled into a false sense of security, and it is important that at each reexamination relevant questions are asked and a proper examination made so that slow and steady development of periodontal disease or secondary caries is recognized.

A typical «simple» treatment plan would be as follows.

1. Reinforce oral hygiene procedures lingual to lower molars.

2. Scale and polish.

3. Replace stained composites as charted (and the dental chart might show two or three anterior composites to be replaced).

A more complex treatment plan is often required for patients who have not attended for some time or where there is a need for a major reassessment of a declining state of dental health. In these cases it is helpful to divide the treatment into stages.

1. Urgent treatment for the relief of pain or other symptoms.

2. Treatment for the stabilization of progressive disease or conditions which may become acute (e.g. temporarily restore very carious teeth, remove necrotic pulps, or extract teeth even if they are symptomless at the time).

3. Assess the cause of the dental disease and begin initial preventive measures.

4. Reassess the patient's response to this initial treatment and decide the broad outline of the future plan. At this stage it may be necessary to decide between a number of alternative solutions of different complexity and cost. For example, the same clinical condition (a badly broken-down mouth with many failing restorations and unsatisfactory partial dentures) may be treated in different patients by one of the following:

• extracting all the remaining teeth and providing complete dentures

• providing extensive restorative treatment with multiple crowns and fixed bridges to replace the partial denture

• a midway position between these extremes with some extractions, some restorations and new partial dentures.

The basis of this broad decision will be the patient's motivation, his or her response to initial treatment and preventive measures, and the cost. It is a crucial decision and one of the most difficult to make. If there is any doubt, it should be deferred or, better still, a second opinion should be sought from a colleague who may be a member of the practice or the clinic or a local consultant. In some cases, for example hypodontia, decisions may need to be made about orthodontic treatment before providing veneers or crowns and bridges.

5. Provide the initial stage of definitive treatment which may be further preventive measures, periodontal treatment, orthodontic treatment, extractions, or other surgical treatment.

6. A further reassessment to evaluate the success of the first stage of treatment and revise the treatment plan as necessary.

7. Provide the final stages of the active course of treatment.

8. Reassessment, maintenance, and reinforcement of preventive measures. The importance of making plans, both simple and complex, and of recording the decisions in the patient's record can be summarized as follows.

• It ensures that the clinician reviews the treatment in the light of all available evidence at the start of treatment and at stages throughout it.

• It is a record for later reference, particularly in complicated cases and after a lapse of time. This is available mostly for the benefit of the patient, but on occasions, when patients complain, it may have dento-legal importance and may protect the dentist against unjustified complaints. In this context, when the treatment plan is complex and expensive, it may be wise to put the advice in the form of a letter to the patient so that he or she has time to consider it and its implications before acceptance or rejection. The letter is also a written record, of which the patient has a copy, in cases where there is a dento-legal problem later.

• It avoids the risk of disorderly and ill-advised management which may arise if treatment is undertaken piecemeal. Unfortunately, this is a danger in clinics which are organized on a rigid departmental basis, so that a logical course of treatment is interrupted by different lengths of waiting lists in each department or by the student's inability to carry out certain items of treatment. In a learning environment some restrictions are necessary, but it is important that the compartmentalized attitudes they engender are not carried over into practice.

Some common decisions which have to be made

Clearly, it is not possible to give guidance on every decision which may have to be made, but the following set of examples illustrates the nature of the decision-making process. The examples are as follows:

• diagnosing toothache

• whether to restore or attempt to arrest and partially remineralize a moderately sized carious lesion and whether to restore or monitor an erosive lesion

• whether to extract or treat a tooth

• which restorative material to use.

Making the diagnosis in a patient with toothache

Although it is necessary to know the characteristic symptoms and signs of a condition, it is also necessary to have a systematic method of diagnosing the cause of symptoms in a patient with toothache.

The history should concentrate on the nature of the pain, its duration, and initiating stimuli. Clues should be followed; for example, chronic sensitivity to sweet foods may suggest exposed dentine rather than any of the other conditions, and chronic tenderness to biting will suggest either a cracked cusp or perhaps chronic apical periodontitis. The past dental history may be of interest in cases where trauma or recent restorations may be the cause.

On examining the patient, the dentist should look for possible causes such as caries, leaking restorations, cracked cusps, or evidence of trauma. Radiographs, vitality tests, and percussion tests are all required in order to be confident of a diagnosis in almost every case. Radiographs may show periapical radiolucencies, failed root fillings, internal or external root resorption, fractured roots, and other possible reasons for the toothache.

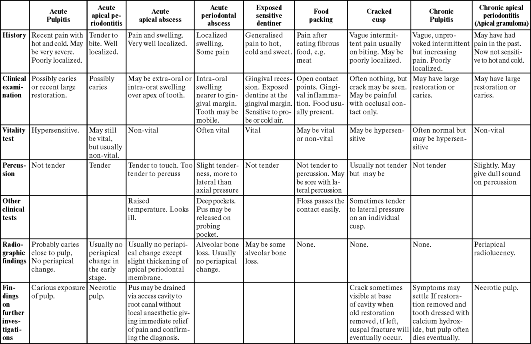

Figure 2 shows the typical interpretation of signs and symptoms in toothache.

Finally, despite having completed a full investigation, there are occasions when the cause of the pain is still not clear. At this point it is wise to reconsider other causes of pain, such as trigeminal neuralgia, but if these can safely be eliminated then, and only then, the dentist should start to remove previous restorations.

A simplistic maxim, but one well worth remembering, is «diagnosis should precede treatment». Far too often busy dentists, pressed for time, feel an obligation to start treating teeth without having made a through diagnosis of the cause of the toothache.

Questions to the text:

1. What are the requirements for completing a dental history?

2. What is necessary to maintain during dental treatment?

3. Who is the final decision on treatment plan taken by?

4. How can the importance of making treatment plans be summarized?

5. What are the ways to diagnose the cause of symptoms in a patient with toothache?

6. Interpret the typical signs and symptoms in toothache as presented in

Fig. 2.

Exercise 12. Prepare topics on your own:

1. Dental services in Russia.

2. My visit to a dentist.

3. My future profession.

Fig. 2. Typical

signs and symptoms in toothache. Unfortunately, not all symptoms fall

precisely into this pattern and clinical judgement and experience is

often needed for their interpretation.

Fig. 2. Typical

signs and symptoms in toothache. Unfortunately, not all symptoms fall

precisely into this pattern and clinical judgement and experience is

often needed for their interpretation.